Why Did We Start The Demo Music Observatory?

Comparing the living standards of musicians and the general population

Comparing the living standards of musicians and the general population

I was contacted during the consultation period of the Feasibility Study of the European Music Observatory. That led to an uneasy series of conversations with the consultants of this project, and a very enlightening series of conversations with European civil servants, music industry organizations, music managers and artists. My main pitch was that every single assumption of this project is wrong.

They started from the assumption that there is hardly any data available on the European music scene – whereas we found while building up CEEMID, errr, a pan-European music data observatory, is that music is one of the most data-driven industries in the world, it is choking in numbers, and the reason why this data is not visible is very different. They were talking about lack of data in fields where we already had about 2000 pan-European indicators ready. (See Introducing the CEEMID Observatory, 9/28/2019 large self-contained html file, takes time to load into browser)

Big data creates injustice

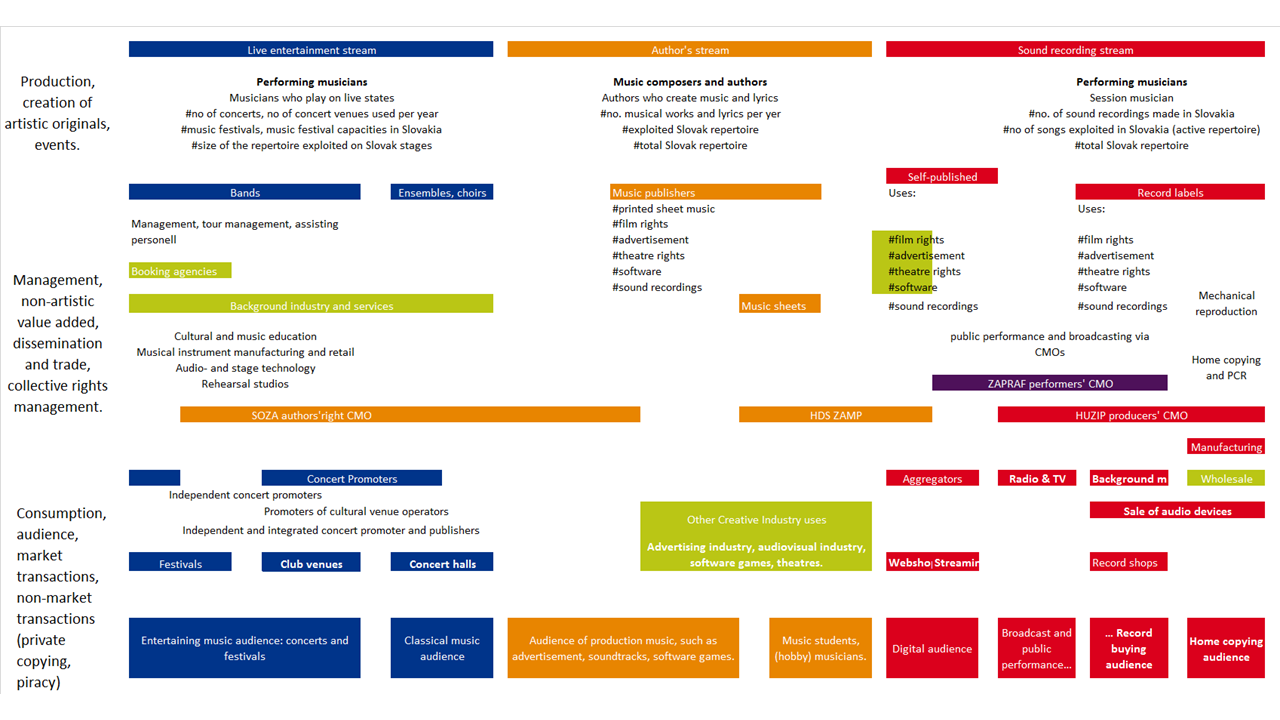

The music industry is scattered: it has the author’s or publishing side, the recording side, a large live music business and usually a very environment for classical (art) music. Within these segments there are hundreds of organizations in each EU country, and each have their own small or large datasets. The music industry has plenty of data, but it is not integrated, and it is often hidden from organizations that may have a conflicting agenda.

The fragmentation of data makes these players easy prey in the era of big data. Companies who monopolise big datasets first and create weapons of math destruction in the forms of algorithms that work for them, can take an unusually large share of the money created throughout the value chain. Proprietary, uncontrolled, big data trained algorithms reinforce inequality — this makes Google’s YouTube, Spotify, but also Netflix in films or Amazon in books so powerful against its competitors, but also against competition regulators or suppliers — in this case songwriters, video producers, filmmakers, book publishers and authors. If their algorithm works against a creator, the creator is doomed, because half of the global sales are driven by secret algorithms.

Big Data vs Small Datasets, Research Automation

The problem of the music industry is not too little, but too much data. Music is drowning in numbers, and it has too little resources to turn much data into valuable information.

Our concept of the European Music Observatory is to pool enough resources to create value for rightsholders, talent managers, venues, festivals and the entire music ecosystem. Most music organization employ 1-5 people, and even the largest national organization, like collective management organizations, fall under the EU definition of small- and medium sized enterprises. They do not have data scientists, market researchers, forecasters. They are small organizations with small research budgets and very little time for researching. Nevertheless, with more than 60 partners in 12 countries we have shown that this is possible:

-

we turned 700 million royalty statements into meaningful indicators about the price and volume growth in 20 European streaming markets;

-

calculated the value gap and the value of private copying in Hungary and Croatia;

-

helped closing the royalty gap in Hungary and Slovakia by helping collective management to significantly increase their royalty collection;

-

helped granting agencies to make more relevant grant calls and designed indicators to measure the impact of their grants;

-

started the creation of local recommendation engines that help the circulation of the small nation repertoires or city scenes in Europe or beyond.

Music Has Data, But You Need A Map

Scattered industries tend to be riddled with conflicts of interests. While working with royalty collection management societies in the last 7 years I often saw that songwriters, producers and performers are often fighting each other for slices of the pie that is just too small. That means that national members of CISAC (GESAC in Europe), IFPI, and AEPO-ARTIS often do not share data with each other, although their income is below any legally acceptable threshold. They have individually very rich datasets that in many jurisdictions just never meet. Labels, small publishers are so little organizations that they do not have a data scientist, let alone a dedicated IT person, or even an HR professional to hire the services of data scientists.

We were able to collect at least 70% of the information content of the planned European Music Observatory, and far more, than most of the 50 data observatories we examined in Europe, because we took an approach inspired in open source software development: continuous opt-in, opt-out data integration, focusing on the synergies that partners can achieve, instead of aiming at endless discussions and compromises on sharing data. We never take away proprietary data from anybody, we just connect data among partners, and enrich it with open data. We would like to guide the industry from hierarchical database planning to the philosophy of open collaboration.

-

We automated most of the research tasks, to make it less costly, less error-prone, and require less labour input. We can automate most of the data collection, data processing, imputation, validation, documentation, reporting, even some modelling.

-

We invested into harvesting the vast open data of the European Union and its member states. In the EU, most taxpayer funded research data is freely available, but at a cost of significant data reprocessing cost. If the data was originally collected to calculate to inflation or monitor tax revenues, it needs to be significantly altered for the music industry to be useful.

-

We have found a way to connect many small data sources and open data. We can create big data from much small data, and deploy analytics, algorithms on collective datasets.