Listen Local: Why We Need Alternative Recommendation Systems

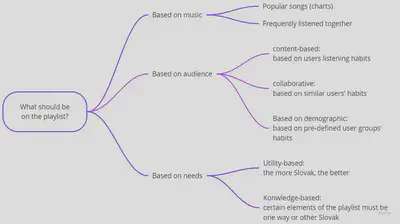

Recommendation systems utilize knowledge about music content and their audiences while also pursuing the objectives or needs of recommenders.

The simplest recommendation systems just follow the charts: for example, they select from well-known current or perennial greatest hits. Such a system may work well for an amateur DJ in a home party or a small local radio that just wants to make sure that the music in its programme will be liked by many people. They reinforce existing trends and make already popular songs and their creators even more popular.

If the recommendation engine is supported by big data and a machine learning system – or increasingly, a combination of several machine learning algorithms – the general modus operandi is to exploit information about both content and users in order to achieve certain goals.

How algorithmic recommendation systems work?

Spotify’s recommendation system is a mix of content- and collaborative filtering that exploits information about users’ past behaviour (e.g. liked, skipped, and re-listened songs), the behaviour of similar users, as well as data collected from the users’ social media and other online activities, or from blogs. Deezer uses a similar system that is boosted by the acquisition of Last.fm – big data created from user comments are used to understand the mood of the songs, for example.

YouTube, which plays an even larger role in music discovery, uses a system comprised of two neural networks: one for candidate generation and one for ranking. The candidate generation deep neural network provides works on the basis of collaborative filtering, while the ranking system is based on content-based filtering and a form of utility ranking that takes into consideration the user’s languages, for example.

What makes these systems common is that they maximize the algorithm creators’ corporate key performance indicators. Spotify wants to be ‘your playlist to life’ and increase the amount of music played during work or sports in the background, during travelling, or active music listening –- i.e. maximizing the number of hours spent using it, and do not let empty timeslots for other music providers, such as radio stations. YouTube and Netflix have similar targets. They are in many ways like commercial radio targets, which want to maximize the time spent listening to the broadcast stream. Radios and YouTube, in particular, have similar goals because they are mainly financed through advertising. For Spotify or Netflix, their key financial motivation is to avoid users’ cancelling their subscriptions or changing it to different providers, such as Amzon, Apple or Deezer.

What is the problem with black box recommendation systems?

What they also have in common is that they do not aim to give a fair chance to each uploaded song, serve equally every artist, or provide whatever equality of chances for English, Slovak or Farsi language content.

They tend to reinforce trends similarly to music charts, but with far bigger efficiency. As the Dutch comedian, author and journalist Arjen Lubach explains the YouTube algorithm, to keep their personal recommendations engaging all the day and all of the night, they create a comfortable universe for the user allows little distraction in. If the user wants to listen to global hit music, or stoner rock, it will never be distracted with anything else.

Zondag met Lubach on Dutch public broadcaster VPRO. Click settings sign to change the language of the captions.

The problem with such hyper-personalized media is that they leave no room for public activities. Public broadcasters, which had a monopoly to television broadcasting in most European countries until the early 1990s, for example, were aiming to air a diversity of news, knowledge and access to local culture. Many countries on all continents have maintained local content guidelines for broadcasting on public, commercial and community television and radio channels, for example, local music and films, and reliable news as a public service. Personalized media-, social media- and streaming platforms do not have such obligations.

-

Black box recommendation systems usually maximize a corporate key performance indicator, and they are not subject to usual public new service or local content regulations that traditional broadcast media is.

-

The goal and the steps that the algorithm is pursuing is not know to content creators, and they do not know when will the algorithm work for their benefit or against them.

Transparent and regulated AI

In our view, utility-based recommendation system can provide a bridge between current, corporate-owned systems that maximize a media or streaming platforms’ business indicators.

Public new service requirements or local content requirements (“national quotas”) set for commercial broadcasting are similar to utility or knowledge-based recommendation systems. A utility-based recommendation system, for example, would prefer from two candidates for a playlist the one that has a Slovak composer, or a performer from Wales, or which has Farsi lyrics.

Our Demo App creates recommendations on the basis of a pre-existing radio or personal streaming playlist that, by choice, contains a pre-defined ratio of music produced in Slovakia, or performed by Slovak artists. We will soon add Dutch and Hungarian choices to this demo, but naturally, we could add any city’s, regions’, province’s our countries preferences into the app.

Our Demo App and accompanying Feasibility Study in Slovakia shows how can a regulator create better broadcasting regulations, learning from the experience with AI-driven streaming platforms, and how can it apply the goals of local content requirements (such as a certain visibility for Slovak or a city-based music) and public service requirements (for example, spreading reliable information or stopping hateful music.)

Access for all

We do not believe that the current heated discussion on the re-regulation of AI and music streaming will solve all the problems of independent artists, bands from ethnic or racial minorities, or otherwise vulnerable producers. New regulation can limit the unintended collateral damage of big data algorithms deployed by big corporations, but they will not bring down the benefits of AI to these creators.

Take the example of the controversial new initiative that let’s artists, labels and publishers to promote their music in exchange for a cut in royalty rates. While felt by many artists injust and even corrupt, it is an answer to the growing need to influence how the recommendation algorithms are promoting certain music at the expense of tens of millions of sound recordings that are not recommended.

We believe that algorithms create value for the users, and if artists are not happy to pay for corporations to influence black box algoritms, thatn they must collaborate and share data, and build large enough data pools so that they can deploy white, transparent algorithms that work for them.

-

Our Feasibility Study shows why it is important that creators have a

control over what data describes their music, their biographies and other information online, because corporate streaming platforms use this information for their algorithms. -

We should that with relatively little effort creators can

pool enough informationto create alternative recommendation systems that follow a more agreeable goal, that is sensitive to local content requirements and more access to new artists, women or black performers, or which suppress hateful lyrics. -

The benefit of an

open algorithmand pooled data is that artists can actively look for audiences in various age groups or in cities that are accessible for them on a performing tour after the pandemic.

Overall, we want to show that regulating black box, private algorithms and data monopolies is only a first step to damage control. Deploying white, transparent algorithms and building collaborative or open data pools can only guarantee fairness in the digital platforms, in recommendations, and generally in the use of AI.

Listen Local is developing transparent algorithms and open source solutions to find new audiences for independent music. We want to correct the injustice and inherent bias of market leading big data algorithms. If you want your music and audience to be analysed in Listen Local, fill this form in. We will include you in our demo application for local music recommendations and our analysis to be revealed in December.