What If Your Stream Count Would Count For The Artists?

Contrary to what many believe, your music streaming history plays a relatively small role in the payouts of the artists whose songs you are listening to. The streaming platforms use a MCPS, or market-centred payout system, which is biased towards large market listeners. Contrary to UCPS, or user-centred payout systems, where all streams by all users are tallied up to determine the final distribution of subscription and advertisement revenues, MCPS uses weighted averaging that very heavily favours major music distributors and the biggest global stars.

We analyze these competition policy problems with Amelia Fletcher and Peter L. Ormosi in our forthcoming publication in a special issue of Competition Policy International, Music streaming: is it a level playing field?. But in the meantime, an interesting impact assessment emerged from France, because the Centre National de la Musique commissioned Deloitte to make an impact assessment on a possible change. Deezer provided a full overview of its 2019 payouts, while Spotify gave a sample of 100,000 artist payouts, and the other streaming services — for example, Apple Music — refused to cooperate with the French government-backed institution. You can read an English language summary and an excellent commentary from Emmanuel Legrand on his blog: User-centric model would not lead to significant changes in the distribution of music streaming royalties.

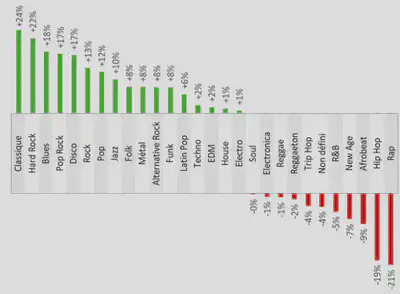

Fair distribution would completely alter the revenues of different genres. The biggest winner would be classical music, but various forms of pop, rock, jazz and disco artists would earn 15–25% more revenue. Currently, rap and hip-hop take about an extra 20% royalty revenue at the expense of these genres.

The streaming providers, which are directly or indirectly part-owned by major labels, are playing down the results, claiming that the difference would translate only to a few euros per artists at the bottom of the pyramid. In a sense, this is true, because streaming royalties are generally very low. But averaging is extremely misleading, because it includes millions of songs that are out-of-date or for another reason are never heard. In fact, entire scenes and labels would earn about 10% more revenue globally, considering that streaming revenues add up to half or even more of their total recording revenue.